November is here, and it is officially the end of the 28th season of fall banding at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory. As the curtain closes on another successful autumn owl migration, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on our time spent occupying the Point during those long autumn nights.

This season we were able to band a total of 103 owls. It wasn’t a record low, but it was significantly lower than what we expected when we started in mid-September. For reference, the average fall owl banding season at Whitefish Point nets 163 Northern Saw-whet Owls (NSWO) alone. The vast majority of our captured owls were NSWOs, coming in at 94 owls. The remaining nine owls consisted of six Long-eared Owls (LEOW) and three Barred Owls (BDOW). Unfortunately, no Boreal Owls (BOOW) graced us with their presence this banding season.

We recaptured three NSWOs, in addition to the 94 owls mentioned above, that had been previously banded. Two of the three were banded here during previous seasons at Whitefish Point. One of those was banded by a good friend almost exactly two years to the day of its recapture. The remaining recapture was an owl banded at the station in Cedar Grove, Wisc. It’s always a treat to recapture an owl banded by someone you know. Sometimes on slow nights, we found ourselves pondering the journeys these owls ventured on — where in the continent they first hatched, if and where they bred, what sorts of trials and tribulations they experienced since they were initially captured.

One may think that walking the same trail 15 times a night every night for a month and a half would become boring and repetitive, yet we failed to find that the case. Each net check provided a chance to become familiar with the local fauna that shared our moss-lined trails through the jack pines and reindeer lichen. Eyeshine from mammals such as mink and white-tailed deer would catch our attention as our headlamp’s beam pierced the creeping darkness that enveloped the Point after sunset. We often found ourselves struggling to balance the desire to gaze up at the brilliance of the Milky Way along with the necessity to watch out for equally gorgeous blue-spotted salamanders meandering across the path.

We couldn’t summarize the fall banding season without addressing the weather. Anyone familiar with this area of Michigan knows to expect plenty of wind and rain when autumn arrives. The wild winds of November famously sank the Edmund Fitzgerald in 1975, after all. This year was no exception, although the presence of southerly winds during the first two weeks of October gave us unseasonably warm nights. We took those warm nights for granted, frequently pining for their return when the temperatures finally dropped.

By the time you’re reading this, the remaining leaves will have fallen and snow will blanket the Point in its characteristic white fluff. A quiet peace will encompass the net lanes until owl banding resumes in the spring. We would like to thank all that have contributed their time, energy, and resources to making the Point the special place it continues to be. Many people keep this area close to their hearts, and after spending the autumn here, it’s obvious why.

~ by Lead Owl Bander Tim Baerwald and Assistant Owl Bander J. Byron De-Yampert

Tim Baerwald has been working as an avian field tech for 10+ years on projects across the country ranging from shorebird banding to raptor counting.

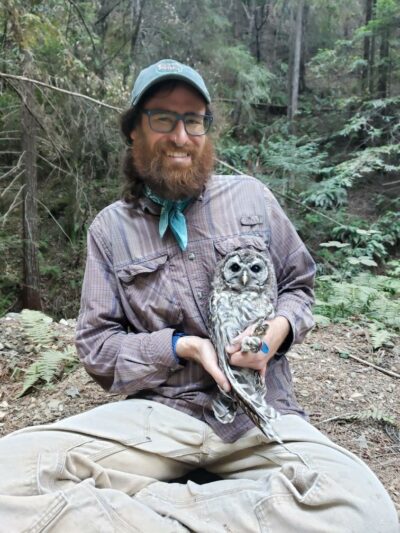

Byron de-Yampert is a Michigan native who has worked on multiple field projects since graduating from Michigan State University a decade ago. He has spent several years banding Spotted Owls for demography projects run by UW-Madison and UC-Davis. He recently finished assisting a graduate student capturing juvenile Barred Owls for a project analyzing Barred Owl dispersals in northern California.

This article appeared in the 2022 Winter Jack Pine Warbler.