CC Stuart Anthony

Collisions with Glass – A serious, preventable threat to birds

Recent studies estimate that nationwide, between 365 and 988 million birds are killed annually by building collisions (Loss et al. 2014), making building collisions the second largest threat to bird populations in the United States. Most fatalities seem to occur at low-rise buildings (16 – 27 bird deaths per year), although every residence is estimated to kill 2 birds each year. The good news is that bird-window collisions are entirely preventable across all building types. Continue reading to learn more about what factors influence bird-window collisions and find solutions to prevent bird deaths at your home or office.

Why do birds hit windows?

Much is still unknown about why birds hit windows, but research is beginning to reveal a clearer picture. We do know that birds cannot see glass and most often strike glass in four common situations:

- The glass reflects a mirror image of vegetation, which a bird seeks to land on (this seems to be the most deadly situation);

- The glass reflects a mirror image of the sky, which a bird believes it can fly through;

- There are potted plants immediately on the inside of the glass, which a bird seeks to land on; and

- There are two parallel glass surfaces (e.g. a glass walkway), which a bird perceives as a clear flyway.

While some birds attack their own reflections in glass, this behavior usually does not result in death.

We can prevent bird-window collisions by making glass more visible and by breaking up reflections on the outer surface of glass.

When do birds hit windows?

Birds strike glass surfaces year-round, but collision rates increase during spring and fall migration when greater number of birds are passing through urban areas, where other factors can make matters worse. Many migrating birds take advantage of safer, more energy-efficient conditions by migrating at night. Light pollution, heavily concentrated in urban areas, has significant impacts on night-migrating birds. Night-migrating birds use stars as part of their navigation system, which results in confusion when birds encounter artificial night lights. Artificial lighting can attract migrating birds down into urban areas, where they become disoriented, or even trapped within bright light beams. As the sun rises, birds that have been lured down into the city are often exhausted and confused after a night spent flying in circles, going nowhere. Unbroken glass surfaces become mirrors, reflecting images of trees and open sky – reflecting a false escape route for a tired bird. Some studies have shown that collision rates are highest between 6 and 9 am, suggesting that reflections are a significant driver of bird-window collisions. Other studies have made connections between the amount of night lighting a building emits and the number of bird-window collisions. Regardless, it is clear that both night lighting and unbroken reflective surfaces play a role in bird-window collisions.

Poor weather, including storms and fog, can result in large numbers of birds colliding with man-made structures, including glass and communication towers.

Are some species at greater risk?

Ruby-throated hummingbirds are frequent victims of window collisions CC El Marto

Studies have shown several species are more vulnerable to window collisions than others. These vulnerable species vary regionally and there may be certain species that are more likely to hit specific building types as well; for example, Purple Finches are frequent victims at residences.

Groups of birds that appear to be more vulnerable include: hummingbirds, shorebirds, kingfishers, waxwings, and warblers.

Some species at greatest risk include: Black-throated Blue Warbler, Ruby-throated Hummingbird, Golden-winged Warbler, Brown Creeper, Connecticut Warbler, Ovenbird, Canada Warbler, Swamp Sparrow, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, and Gray Catbird.

For a more complete list, see Loss et al. 2014.

How can I prevent window collisions?

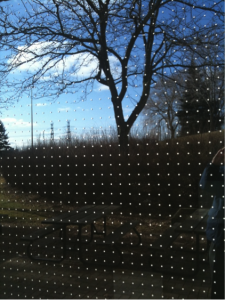

Feather Friendly Tape applied to the outer window surface breaks up a reflection of a nearby tree.

- Break up reflections across the entire outer surface of the window.

- Place bird feeders either less than 3 feet or greater than 30 feet away from windows.

- Move indoor plants several feet away from windows.

- Reduce artificial night lighting.

Reflections. More studies are suggesting that high amounts of vegetation near windows (which reflect that vegetation) results in more bird-window collisions. Breaking up that reflection on the outer surface of the glass is critical to reducing window strikes. Temporary stickers or paint can be applied to the outer surface of a window to deter bird strikes, but these must be applied correctly – hawk silhouette stickers do not work. You can apply dense patterns of window stickers (2 – 4 inches apart), American Bird Conservancy’s Bird Tape, other CollidEscape products, make or purchase your own BirdSavers Zen Wind Curtains, or Feather Friendly dot tape. For a full list of tested collision prevention products, visit the American Bird Conservancy Website.

Night Lighting. Birds migrating at night are attracted to artificial sources of light, particularly during periods of inclement weather. As birds approach the lights of tall buildings, communications towers, lighthouses, floodlit obstacles, and other lit structures, they become vulnerable to collisions with the structures themselves. Even if collisions with these structures are avoided, birds are still vulnerable.

“Once inside a beam of light, birds are reluctant to fly out of the lighted area into the dark, and often continue to flap around in the beam of light until they drop to the ground with exhaustion. A secondary threat resulting from their aggregation at lighted structures is their increased vulnerability to predation. The difficulty of finding food once trapped in an urban environment may present an additional threat.” [www.flap.org]

Here are a few simple steps you can take or encourage other to take:

- Turn off unnecessary indoor lights or pull shades at night.

- Turn off decorative landscaping lighting.

- In office buildings, turn off lighting on the outside perimeter offices and use only interior office lights if needed. If lighting must be left on, use curtains to block light from escaping.

- For new outdoor lighting, purchase fully shielded lights approved by the International Dark-Sky Association.

Find out if your city has an outdoor lighting law that limits light pollution. Speak up locally or to your state representatives about the impacts of unnecessary night lighting on migratory birds. Encourage your city to pledge to reduce lighting during spring and fall migration through Safe Passage.

How can I get involved with local bird-window collision monitoring?

Across Michigan, several local efforts to survey for bird-window collisions have emerged. Washtenaw Safe Passage, Detroit Audubon, and Audubon Society of Kalamazoo are all involved in measuring and/or preventing bird-window collisions. Starting in 2018, Michigan Audubon worked with volunteers in the downtown Capital area and Michigan State University to monitor for bird-window collisions. Please contact your local Audubon chapter or university to find out if a local effort exists or how to start one. Contact us if you would like assistance in starting a new monitoring program.

If you have found a victim of a window collision, you can report your sighting to the Global Bird Collision Mapper, a web app from the Fatal Light Awareness Program that allows anyone, worldwide, to contribute to raising awareness of and documenting bird window collisions. You may also submit your records to our MI Bird-Window Collisions project on iNaturalist. You will need an iNaturalist account to submit your sighting (Bonus: The iNaturalist app makes entering observations quick and easy!). Please include any information you can about the window and the surroundings. It is okay if you cannot identify the bird; other iNaturalist users can suggest a species after you submit photos. Your observations can contribute to a broader understanding of bird-window collisions in Michigan.

Volunteer monitors for Michigan Audubon routes:

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, no bird specimens from window collisions will be collected at this time for Michigan Audubon projects. Interested volunteers may still monitor for window collisions in their local area (e.g. at your home or on your walking route you take for exercise), using caution and adhering to the current COVID-19 restrictions and/or precautions. You may enter information about birds found as a result of a window collision to: https://birdmapper.org/app/.

If you find an injured bird, contact your local wildlife rehabilitator. Michigan DNR maintains a current list of licensed rehabilitators.

During a typical season, volunteers are needed to walk collision monitoring routes during spring and fall migration: March 15 – May 31 or August 15 to October 31. Survey routes typically have a few buildings, and volunteers should expect to survey their route 2 to 3 times per week.

If you are interested in volunteering, please fill out the Michigan Audubon volunteer application.

What to do if you’ve found a live bird that has hit a window:

If a bird strikes a window and survives, it is likely dazed, disoriented, or in shock. In this state, the bird may be very vulnerable to predators. If possible, gently pick up the bird and place it in a breathable paper bag or small box with a lid or towel on top and take it to a rehabilitation facility immediately for steroids, anti-inflammatories, and supplemental oxygen.

Do not try to feed injured or baby birds any food or liquid.

You can find a local wild bird rehabilitator at http://www.michigandnr.com/dlr/.

Resources

Visit the links below to learn more about making your city, town, community, neighborhood, or home safer for our feathered friends.

- Effective Window Solutions from the American Bird Conservancy

- Bird-friendly Building Guidelines from the American Bird Conservancy

- How to help a bird injured from a window strike

Bird-window collision monitoring programs making a difference for city birds:

Have Questions?

If you would like to learn more about making your community more bird-friendly, please email [email protected].