My dear friend, Lynne, has deep, multigenerational ties to Whitefish Point. Over the decades, she has watched the Point change from a truly remote and wild place to a destination thronged by tourists in the peak season. She is fearful that “the Point will be loved to death.”

I, too, watched the Point change as its uniqueness was coveted for commercial purposes and passionately defended by bird enthusiasts and environmentalists. That the Piping Plover reign over the tip of the Point that was once coveted for a campground seems almost miraculous. I will never forget the thrill of hearing the piping of plovers carry over the water when they returned to the Point.

Probably since the first Native Americans camped on the shores of Whitefish Point, it has captured the heart of anyone who visits. It offers spectacular sights from kettling hawks to a gale-frenzied Lake Superior crashing against cobblestone beaches. I understand why rockhounds, boat nerds, maritime history buffs, stargazers, researchers, generic tourists, and birders flock to Whitefish Point (pun intended).

Many who visit the Point likely do not fully realize that its fragile ecosystem is a big part of what draws them there. So, if you come to Whitefish Point, park your vehicle in an assigned space, stay on the trails, stay off the dunes, let the rocks lie and the plants grow, leave your drone in the car, know that the mosquitoes and the flies belong there, take your trash with you, enjoy the hard work that went into preserving the historic light station, and cherish the birds. Be gentle. And please, don’t love the Point to death.

~ by Bridget Nodurft

Bridget Nodurft is a long-time advocate and volunteer for Whitefish Point and a Whitefish Point Preservation Society member.

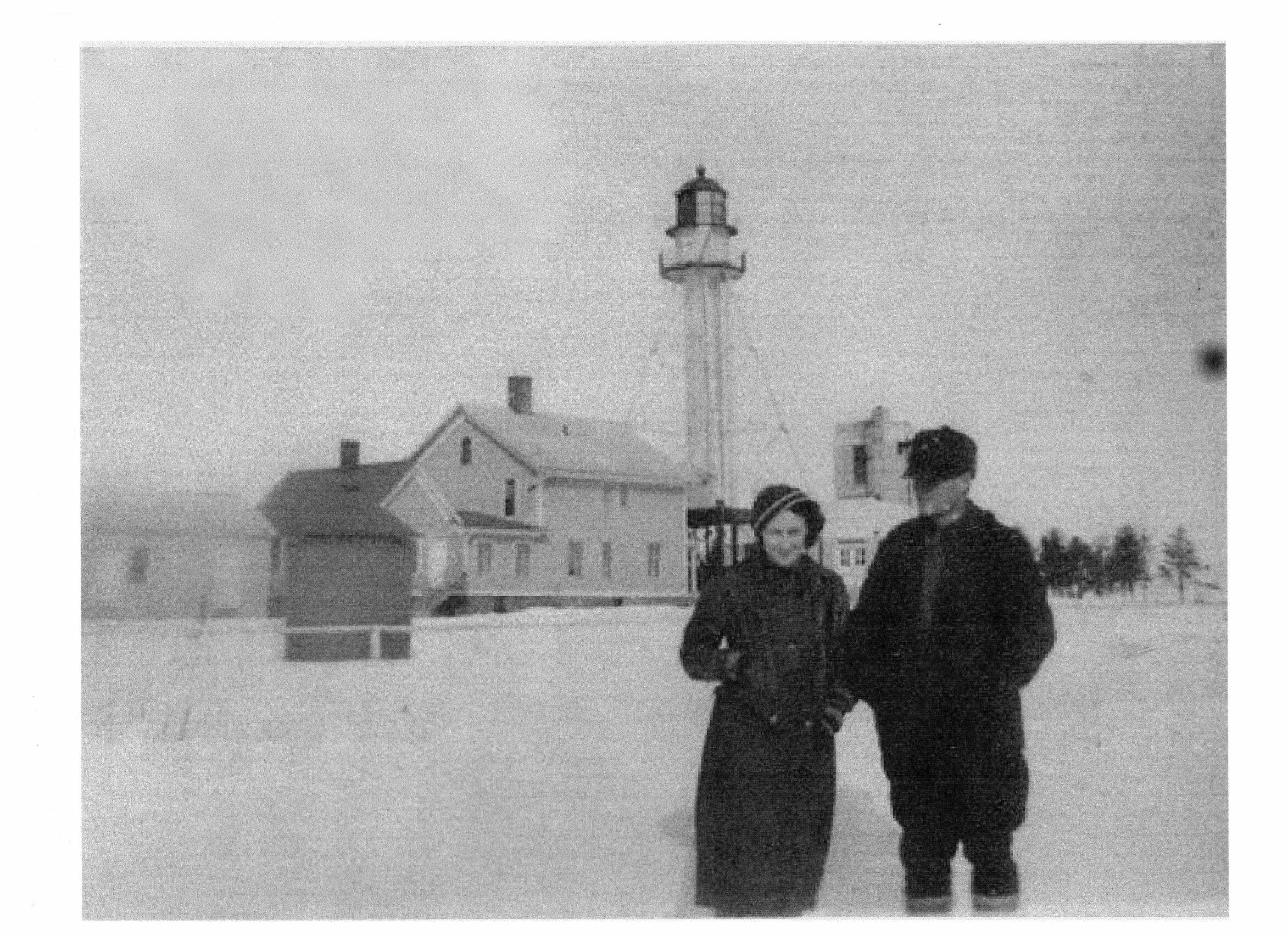

Featured photo: Lynne’s mother at Whitefish Point in 1939.

This article appeared in the 2021 Spring Jack Pine Warbler.