A Northern Saw-whet Owl banded at WPBO. Photo by Kate Maley

Eight out of ten Americans will never live in a place where they can see the Milky Way. While this is simply another way of stating that the majority of the population of the United States lives in urban centers, it also seems to represent a larger disconnect with the nocturnal world. When describing life as an owl bander, many people have told me, “You walk around the woods at night? I don’t think I could do that!”, which is fair. And while I may miss out on some pretty spectacular fall colors and diurnal migration, walking hundreds of miles in the dark (admittedly in circles) offers a unique perspective of the Point.

On a clear night, the night sky at Whitefish Point is nothing short of spectacular. Not only can you see the Milky Way, but also the occasional meteor or line of SpaceX’s Starlink satellites as they streak across the sky (this was a new one for me). Throughout the season, the moon oscillates between being bright enough to make navigating the trails easy even without a headlamp and being so dark it is difficult to tell where the treetops end and the sky begins. Headlamps help highlight signs of wildlife — eyeshine reveals the red fox hiding in a stand of jack pines, subtle flashes of color draw attention to salamanders as they prowl the trails, and fresh tracks in the sand allude to a small American black bear that passed through earlier in the day.

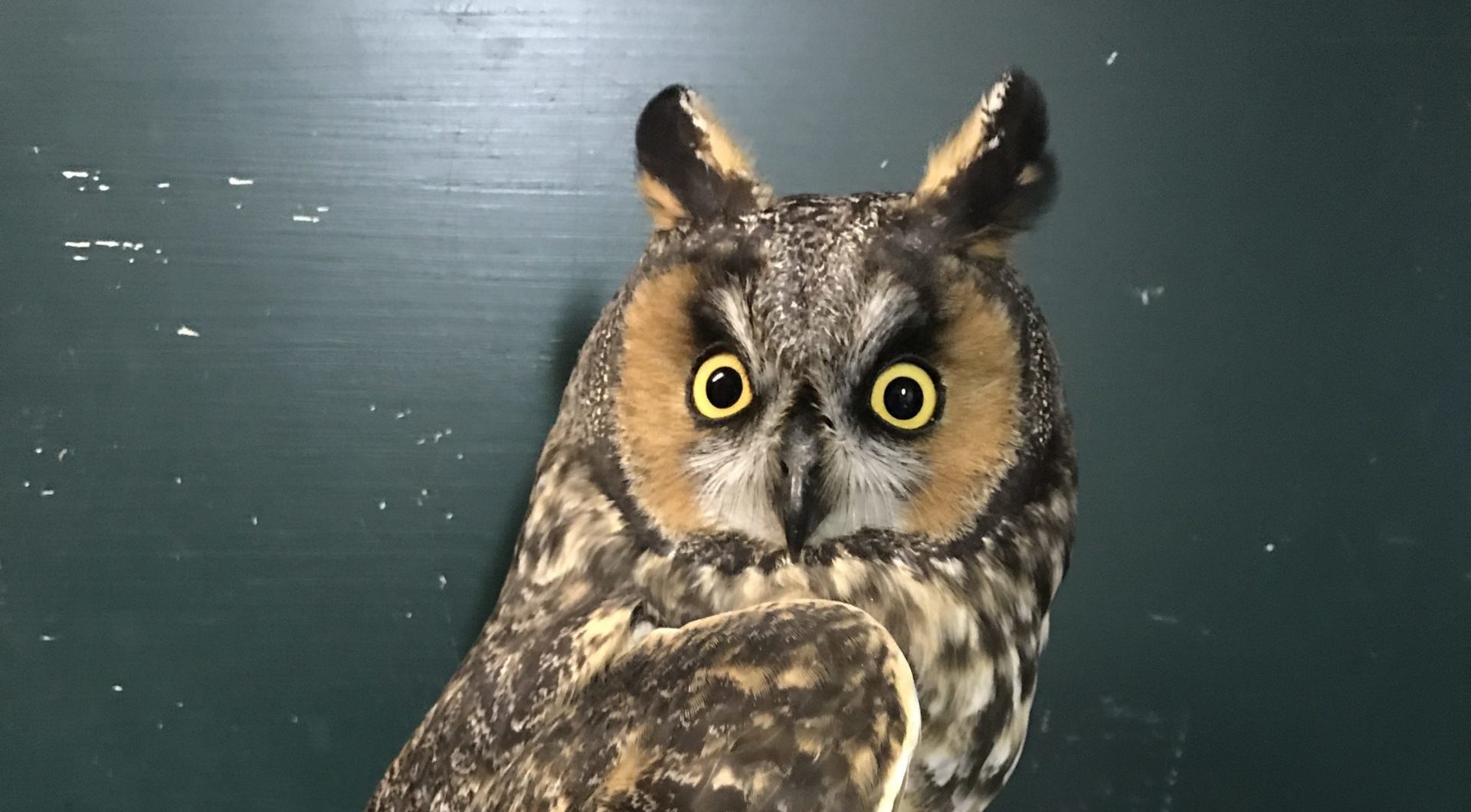

Long-eared Owl. Photo by Kate Maley

There are nights when the loudest sounds are made by falling leaves hitting the ground or migrating birds calling as they fly overhead in untold numbers. On those nights, you can hear the waves switch to the bay side, even before you can perceive the shift in the wind direction through the trees. At times, most noises are drowned out by a ship passing by, close enough to sound larger than life in the dark.

Then, of course, there are the owls. On quiet nights you can sometimes listen to the soft “tooting” of saw-whets or the more jarring “who cooks for you?!” of a Barred Owl passing through. If you’re lucky, you might even hear the soft shifting of bark and faint woosh of wing beats before an otherwise silent flight takes an owl deeper into the woods. As owl banders, we are fortunate enough to get a unique look at these charismatic species by collecting data on individuals and population demographics. During the fall of 2020 alone, we were able to band a total of 274 owls: 257 Northern Saw-whet Owl, eight Long-eared Owl, seven Barred Owl, and two Boreal Owl. Among the saw-whets, 11 had already been banded at another site or during a previous season at WPBO, adding to our collective understanding of migratory movements and timing.

Spotted salamander. Photo by Kate Maley

Amid an unpredictable year, I am grateful to have had the opportunity to spend the fall walking around the woods of Whitefish Point at night. With the dark came a narrowed focus and sense of peace balanced by the excitement of spotting a new species of salamander or banding an owl. I am also grateful to all those involved in protecting that which makes Whitefish Point and WPBO so special by day — but especially by night.

~by Kate Maley, Whitefish Point Bird Observatory 2020 fall lead owl bander

This article appeared in the 2021 Winter Jack Pine Warbler.

Kate discovered a love of birds and fieldwork while attending the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Since then, she has been fortunate enough to work with birds ranging from Golden-winged Warbler in her home state of Minnesota to Greater Ani in Panama.

Whitefish Point Bird Observatory is a program of Michigan Audubon.

Located 11 miles north of Paradise, Whitefish Point Bird Observatory is the premier migration hot-spot in Michigan. Jutting out in Lake Superior, Whitefish Point acts as a natural migration corridor, bringing thousands of birds through this flyway every spring and fall. With its wooded dune and swale complex, distinctive to the Great Lakes region, the Point witnesses a huge diversity of migrants. Home to numerous rare breeding birds, this Globally Important Bird Area has recorded over 340 bird species. Research conducted at WPBO significantly contributes to an ongoing effort to increase knowledge of bird migration, encourage public awareness of birds and the environment, and further critical bird conservation.

There are three owl banding seasons each year (March 15 – May 31, July 1 – August 25, and September 15 – October 31). Learn more about WPBO owl research efforts here and follow the owl banders’ blog to stay up-to-date while they are hard at work.