Twice a year, in spring and fall, we are witness to an extraordinary biological marvel: bird migration. For birds, migration is the seasonal journey to and from breeding and non-breeding (wintering) grounds. We only see part of it — most migration occurs over our heads in the night skies. Migratory birds, like warblers and hummingbirds, are passing through Michigan on their way north or south. This stopover is an important part in the life of a bird that needs quick access to food, water, and protection as it refuels for the journey.

Our early understanding of migration was based on technology of the times: banded bird resightings or observations of birds flying across the face of a full moon. Recent advances in science and technology have improved our understanding of migration. By equipping migrating birds with radio or satellite transmitters, using highly sensitive pressure zone microphones to record birds calling overhead, or deciphering weather surveillance radar images for birds, scientists have been able to study bird migration in detail, observing and analyzing movements of individual birds during flight.

During flight, some species maintain contact with each other by emitting night flight calls. These high-pitched notes of short duration function to keep the group together and synchronized in flight. We have learned that many more species migrate during the night than previously thought. There are advantages to flying at night. Migrating birds expend energy for flight, and the night air provides a cooler, more humid atmosphere than the day. Air currents are more stable, and (aerial) predators are few during the night. Some migrants will fly the entire journey without stopping. Other species will stop along the way, foraging during the daylight hours to replenish their energy reserves. But flying at night can be a challenge. Unable to use visual landmarks or cues from the sun to navigate, nocturnal migrants rely mainly on the constellations, the moon, the earth’s magnetic field, and prevailing winds to guide them in the right direction.

Migration is not easy; not every bird survives the journey. Approximately half of the birds hatched in the spring will not return in the fall. Poor health, disease, lack of stamina, savvy predators, and unfavorable weather impact a bird’s ability to survive migration. Since the mid-20th century, consequences of climate change and land-use changes have begun to impact the quality of stopover habitats. Moreover, the benefits of migration outweigh the risk to those individuals who survive the journey.

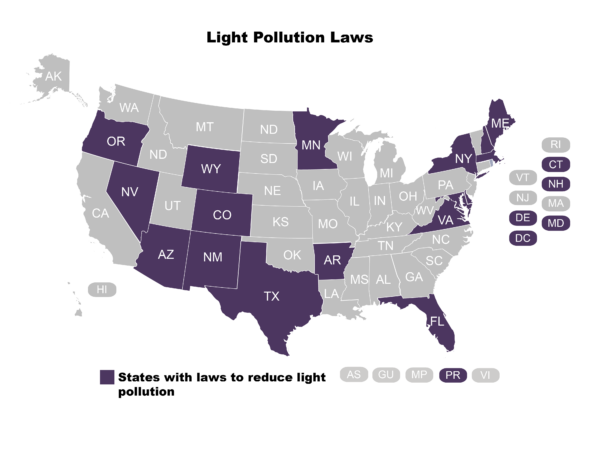

At least 19 states, the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico have laws in place to reduce light pollution. The majority of states that have enacted so-called “dark skies” legislation have done so to promote energy conservation, public safety, aesthetic interests or astronomical research capabilities. Municipalities in a number of states have also been active on this issue, adopting light pollution regulations as part of their zoning codes.

Image source: https://www.ncsl.org/research/environment-and-natural-resources/states-shut-out-light-pollution.aspx#State%20%20Laws

Although mortality is a natural part of life, the number of birds in the U.S. has declined dramatically since the 1970s and is far lower than expected from natural causes. Rosenberg et al. (2019) published a sobering report in the journal Science, documenting the decline. Why is this happening? In addition to the multiple threats already mentioned, birds are at risk from interactions with the built environment: e.g., cell towers, power lines, wind turbines, and reflective or transparent glass in buildings. In addition to being a physical barrier, many of these manufactured structures are illuminated by artificial light at night (ALAN) and create a sensory barrier as well.

Problems with ALAN and nocturnal migrants are not new. In the early 1900s, lighthouse keepers would often find scores of bird carcasses on the ground, especially after a foggy night. Airport ceilometers had the same effect, causing mass mortality on foggy nights during fall and spring. But the world is becoming brighter and brighter. Artificial light at night has increased by 6% annually from 1947 to 2000 (Cinzano and Elvidge 2003).

When birds encounter artificial light at night during migration, the light can overwhelm the natural cues they rely on. Different frequencies of light (colors) interfere with a bird’s ability to visualize the earth’s magnetic map. On nights with low cloud cover blotting out the constellations; on nights with little to no moonlight; on nights where building towers are illuminated with colorful lights; in areas where light beams are projected skyward — these conditions are all problematic for birds migrating at night. Artificial light does not kill birds directly, although an occasional bird may crash into a building or the ground. Birds become disoriented and may fly in the wrong direction. More frequently, light will pull birds off course, wasting their energy on unexpected detours, and cause them to land in inappropriate places — like neighborhood sidewalks.

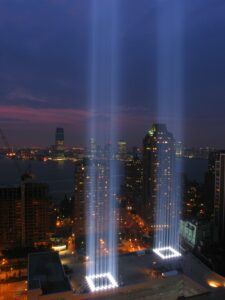

The Tribute in Light in New York City is monitored to make sure birds don’t get “trapped” in its beams while migrating at night.

Photo by tatslow | Flickr CC

Our research and monitoring at NYC Audubon have helped to understand further how ALAN affects airborne birds’ behavior during their fall migration south. Every Sept. 11, New York City honors the memory of those who perished or were injured in the 2001 World Trade Towers attack. Two beams comprising 88 7,000-watt xenon lights are projected skyward from the rooftop of a parking garage in lower Manhattan. Made possible by the 9/11 Memorial & Museum and Michael Ahearn Production Services, the Tribute in Light is poignant and inspirational. Light gradually appears as the sky darkens on the night of the 11th. The beams glow throughout the night, fading as the sun rises in the morning of the twelfth. Since its inception, NYC Audubon staff and volunteers have been monitoring the beams of light, looking for birds “trapped” in the beams during their fall migration.

NYC Audubon scientists can authorize turning off the lights if migratory birds are in crisis, allowing the birds to move away before the lights are turned back on. In 2017, Van Doren and others (including myself) published the results from many years of observations and radar analysis. We were able to show that the strong beams of light directly affected the behavior of migratory birds flying that night. Even when the stars shone brightly, birds were attracted to beams from up to 7.5 miles away. They slowed their flight, changed direction, and vocalized more frequently. All these activities used precious energy that the birds had stored for their migration. As soon as the lights were extinguished, the birds resumed their original flight behavior. Turning out the lights was a simple and immediate solution and has certainly saved the lives of thousands of birds over the years. More of a challenge is to have the entire city go dark for bird migration. To experience the amazing effect of darkness over a larger area, visit one of Michigan’s seven designated Dark Skies parks. “Lights Out” programs provide many useful suggestions for building owners and homeowners, from turning out unnecessary exterior lights, lowering shades at night, turning off decorative lighting, to using task lighting rather than overhead lighting. (Find more details at michiganaudubon.org/bfc/safe-passage-great-lakes.)

Artificial light is one part of the problem. The other part is buildings and glass. How are ALAN and glass threatening bird populations? Intense beams of light or broadscale light pollution draw the birds into the area. Reflective glass kills or stuns them. Simply stated, birds do not know that glass is a solid barrier. They do not know the difference between a tree reflected in a pane of glass and the tree itself. My colleague, Christine Sheppard at the American Bird Conservancy, says, “Birds don’t understand architecture.” Think about it: Birds evolved about 100 million years ago, but the process to make large panes of smooth glass was only invented in the 1950s!

Monitoring data collected by my team at NYC Audubon confirms the issue. We estimate that about 243,000 birds die each year in New York City alone. In 2014, Scott Loss and colleagues analyzed bird/window collision datasets from across the country, estimating that 500 million to 1 billion birds die each year in the U.S. because of collisions with glass. This degree of mortality is a population-level conservation issue. The good news: collision risk can be reduced. By using less reflective glass, and/or adding fritted or etched or ultraviolet patterns, glass can be made more visible to birds. One building we were tracking in Manhattan, the Jacob K. Javits Convention Center, was the biggest bird killer that we monitored. After replacing the building envelope with bird-safe glass, they reduced collisions by more than 90%.

Homeowners can use a temporary exterior treatment to make their windows more visible to birds. (I don’t wash my windows! That helps.). Exterior blinds, screens, or zen wind curtains work, too. Fixing buildings is not as simple as flipping a switch, but it can be done. (For more information about bird-friendly glass, visit The American Bird Conservancy website Glass Collisions: Preventing Bird Window Strikes | ABC (abcbirds.org).

The good news is, there are solutions.

Some cities or communities have voluntary policies. Others, like Ann Arbor, have enacted lighting ordinances. NYC has bird-safe building legislation. Lighting and bird-friendly glass are both addressed in the LEED (Leaders in Energy and Environmental Design) standards of the U.S. Green Building Council.

In the meantime, there are steps you can take today to save birds right now.

- Turn off exterior lights at night, especially during migration. Lights Out campaigns provide immediate solutions to the problem of ALAN. These programs are most effective when large numbers of buildings commit to the program. The added benefit is, turning out the lights saves money.

- Use bird-friendly glass or window treatments that birds can see.

- Become an advocate for Lights Out. Get involved in your local Audubon chapter. Learn more about dark sky initiatives through the International Dark Skies Association.

There is a lot to do, and it can be done — must be done.

World Migratory Bird Day

“Dim the Lights for Birds at Night!”

May 14

Year after year, hundreds of events celebrate World Migratory Bird Day across the globe. Every event is unique and as diverse and creative as the people and organizations involved. This year the theme is “Dim the Lights for Birds at Night.”

WMBD events occur in all corners of the world and involve and inspire thousands of people of all ages and backgrounds. There are no limits on creativity! Past activities and awareness-raising events have included birdwatching tours, online educational workshops and exhibitions, webinars, festivals, and painting competitions, which have been organized at schools, parks, town halls, education centers, and nature reserves.

Visit worldmigratorybirdday.org to learn more about this year’s theme, find events in your area, or register an event of your own.

Susan Elbin, Ph.D., is scientist emerita at NYC Audubon, having retired as Director of Conservation and Science in December 2019, where her research focused on urban ecology — conservation of migratory landbirds and migratory and nesting waterbirds. She has been active in the field of avian ecology, within the U.S. and internationally, for more than 40 years. Elbin is a long-term active member of several professional ornithological societies: the Ornithological Council (past chair), the Waterbird Society (past president), the American Ornithological Society (elected member), and the IUCN Stork, Ibis and Spoonbill Specialist Group (member).

Susan holds an MS degree in Ecology (Pennsylvania State University) and a PhD in Ecology and Evolution (Rutgers University). While adjunct professor at Columbia University, she designed and taught courses in ornithology and migration ecology and has mentored many students over the years.

After her retirement, Susan and her husband, Greg, moved to Grand Ledge, Mich., to be closer to their daughter Rachel’s family. Susan continues her involvement with NYC Audubon and with the Bird-safe Building Alliance. She is a consultant on bird-friendly building design. Locally, in Michigan, Susan has participated in USFWS Sandhill Crane surveys and has given guest lectures for Michigan State University and Michigan Audubon. She has recently become captivated by a Turkey Vulture roost off of M-100 that has been active for more than 20 years.

References

Cinzano, P. and C. Elvidge. 2003. Modelling Night Sky Brightness at Sites from DMSP Satellite Data. 10.1007/978-94-017-0125-9_3.

Loss, S.R., T. Will, S.S. Loss, P.P. Marra. 2014. Bird–building collisions in the United States: Estimates of annual mortality and species vulnerability. The Condor:116, 8-23.

Rosenberg, K., A.M. Dokter, P.J. Blancher, J. R. Sauer, A.C. Smith, P.A. Smith, J.C. Stanton, A. Panjabi, L. Helft, M. Parr, P. P. Marra. 2019. Decline of the North American avifauna. Science 10.1126/science.aaw1313.

Van Doren, B.M., G. Kyle, A.M. Doktor, K. Holger, S.B. Elbin, and A.Farnsworth. 2017. High-intensity urban light installation dramatically alters nocturnal bird migration. P Natl Acad Sci USA 114: 11175–80.