Mike Bishop was a faculty member in the Department of Biology at Alma College for roughly 20 years. He taught biology, ornithology, and scientific methods, all while being an advocate for Whitefish Point Bird Observatory and an active board member for Michigan Audubon. He retired in the summer of 2020 and since then has been volunteering at Forest Hill Nature Area and running rampant in the woods chasing birds.

Recently I was able to catch up with him to talk about his experiences with birds, conservation, and education.

Karinne (KT): Can you describe your journey as a birder?

Mike (MB): I was an animal nerd when I was little. My first big love was dinosaurs, but I quickly realized that I was never going to be able to hold one, so I shifted to insects. After I caught my first snake, I fell in love with reptiles and amphibians — snakes, box turtles, salamanders, and frogs. Sometime in late junior high, I got interested in bats before finally discovering birds. In tenth grade, I first got interested in hawks but very quickly became nuts about all birds. So, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth grade were all about birds for me, and that never really changed. When I started attending the University of Cincinnati for my undergraduate studies, I immediately found out which faculty members were conducting ornithology-related research. They put me in contact with Jim Davis, who was at the time a graduate student studying Belted Kingfishers. I spent the next several years of my undergraduate at UC working with him, looking at nest building, territoriality, creekside foraging habits, and the efficiency of the birds in finding resources along the creeks in southern Ohio. It was a blast!

Then, I moved to Texas and obtained a teaching certificate from the University of Texas at Austin in the hopes of working in environmental education. During that time, I also worked as a naturalist for several years at environmental summer camps for kids. After teaching eighth-grade earth science at Austin Public Schools for four years, I went to Texas State University to obtain my graduate degree in ornithology.

After getting my banding permit, I started working at Alma College and banding at their ecological station. During my years at Alma, I had many undergraduate students — both birders and non-birders — that worked with me. Looking back, it wasn’t a straight path that led me to Alma, but I certainly learned a lot along the way.

KT: Why is bird banding important to you?

MB: In high school, I met Worth Randall, a hawk bander, and thought that banding was the coolest thing in the world! Banding allows us to study population dynamics and life history. By marking birds, you can distinguish individuals in the population to learn about physiological changes, maturation rates, and longevity. Much of what we know about migration routes and timing has come from banding studies. It’s a really useful and effective, albeit tedious, tool. Even though it’s changing dramatically with the advent of transmitters, there will always be reasons to band individuals.

Honestly, my big draw to it was being that little kid that wanted to hold an animal. Once I fell in love with birds, I really wanted to be able to hold them and examine them. Banding allowed me to fulfill that desire.

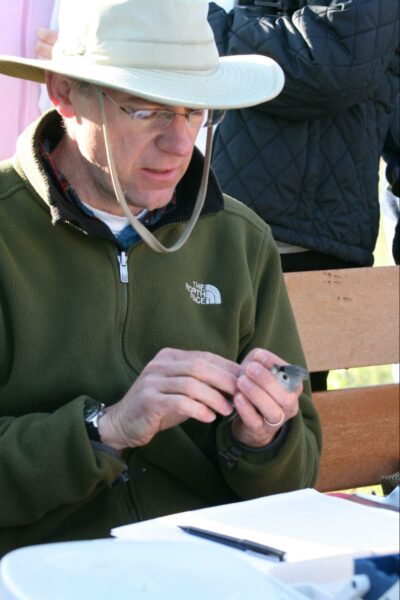

Mike Bishop processes a Tufted Titmouse at the Chippewa Nature Center’s Dragonfly Marsh banding site.

KT: What happens to the morphological data that you collect?

MB: Currently, I’m studying molt sequences in the birds living in the Alma area. This information can help us better determine the age of birds by looking at which feathers are retained over time. I also have an 18-year-long American Kestrel project looking at winter site fidelity. Alma, Mich., is about the northern limit of the kestrel wintering range. We’ve discovered that their behavior in the wintertime is dramatically different from their behavior down south, where most of the research on wintering kestrels has been done. They are highly territorial further south, while up here, they are mostly nomadic. Finally, I’ve got 20 years of banding data that I want to mine in hopes of finding hidden gems.

KT: What role can avid birders play in bird and environmental conservation?

MB: One of the most valuable things birders can do is talk to other people about birding. While it’s great if those you speak to become birders, the primary goal should be to make people aware of some of the issues facing birds and why bird conservation is so important. Talk about why you like birds, why birds are exciting, why some birds are in peril, and why you should keep your cat indoors. The recent paper, “Decline of the North American avifauna,” revealed the loss of three billion birds since 1970. It has made a major impact on many people, even those that may not consider themselves nature lovers.

Also, the advent of eBird has been revolutionary. Additionally, the North American Breeding Bird Survey, Christmas Bird Count, and Project Feederwatch are all great ways that amateur birders can contribute to the field.

KT: What can organizations like Michigan Audubon do more of in the future?

MB: Educate, educate, educate. It comes back to just making people aware. Anything an organization can do to educate people about the environment does two things: It brings a lot of these issues to the forefront, and it sparks interest. When people spark an interest in something, they develop an appreciation and take ownership of it, and then they are much more willing to fight to preserve it. We also need to work to make birding a more inclusive activity and welcome birders of all backgrounds.

KT: What advice can you give young birders?

MB: I’ve noticed that many organizations are seeing attrition of membership, and most of the members are on the older side. Even professional organizations aren’t recruiting younger members like they used to. I firmly believe that young birders are the future ambassadors of bird conservation, and I am extraordinarily interested in reaching those kids because I know they’re out there.

In terms of specific advice, meet and talk to as many people as you can. When I was young, I was constantly finding the people who were doing the kind of work I was interested in and writing them letters — almost all of them wrote back! It’s true; sometimes, you’re going to get nothing. However, as an academic myself, the few times I had high school students or younger contact me, I was absolutely going to respond. Lastly, birding is a skill. To improve, you have to go out and bird. The one area of birding that I see a lot of people neglect is learning calls and songs. In a breeding bird survey, you’re doing everything by song, and there’s a lot of fieldwork like that.

My involvement with the Michigan Young Birders Camp and the Michigan Young Birders Network (MYBN) has been reinvigorating for me. I had gotten to the point where I really just didn’t feel like birds were something young people cared about. Fewer and fewer younger kids were coming through the program at Alma that had a previous interest in birds or even an interest in nature. The MYBN has really gotten me excited that there are kids out there that are really into birding. I’m constantly lurking on the MYBN Discord and love hearing their discussions about artwork, local organizations, or bird walks. I needed to hear about the schools or programs that they are interested in applying to or what they want to do when they graduate. For me, that’s been a lot of fun. It has allowed me to step back and think about how I can assist them. We need more of them, and I want to help with that as much as I can.

~ by Karinne Tennenbaum, Michigan Young Birders Network

Featured photo: Mike Bishop processes a Gray Catbird for banding.

Karinne Tennenbaum is a senior in Ann Arbor, Mich. Although she has many hobbies and interests, birding tops the list. She has her own birding podcast and enjoys birding at Skyline High School in Ann Arbor.

This article appeared in the 2021 Summer Jack Pine Warbler.