Skye Haas, Spring Field Ornithologist, and Gary Palmer, Spring Hawk Counter, on the Hawk Deck at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory.

PARADISE, Mich. – Each spring for nearly 40 years, hawk and water bird counters have perched themselves at wooden shacks overlooking Whitefish Point near Paradise, Mich., in the Upper Peninsula. For eight hours each day, in all but the most extreme weather conditions, they have kept a running tally of each bird species flying overhead at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory (WPBO).

In the past, hawk counters peered through scopes and binoculars and made pencil marks on a printed checklist of bird species common to the region to track the number of birds flying by. At the end of each 8-hour shift, the counter would then retire to a nearby office at the research station and manually enter the data from their tally sheet into a computerized spreadsheet.

This season, counters such as the Spring Hawk Counter Gary Palmer and Spring Field Ornithologist Skye Haas have added Android tablet computers to their field gear and are testing a new tool that not only speeds up this cumbersome data collection and archival process, but also allows interested birders from around the globe to simultaneously access this data in real-time. “It’s pretty incredible to think that I can see a pair of Golden Eagles fly over my head on this small and remote peninsula jutting out into Lake Superior, click a few buttons to record my sighting, and an interested birder or researcher in Detroit or Denmark can easily access information about this bird activity,” says Palmer.

Researchers at WPBO are partnering with Dunkadoo, a non-profit that provides research tools to help scientists collect data in the field. Built on years of collaboration with biologists doing research ranging from California Condor monitoring in California to bat studies in South Texas to seabird counts on the coast of Maine, the Dunkadoo app and integrated online management tool are connecting research efforts with the public and scientists in ways researchers at Whitefish Point could never have imagined possible a hundred years ago.

Established by Russell Conard and Carol Goodman, two passionate environmentalists who also happen to be software developers, Dunkadoo is creating new tools and technology to make scientists more effective and bring their message to the public. “We often get asked about the name Dunkadoo,” said Goodman, current chair of the organization who has spent more than 20 years building software for the automotive industry. “We wanted something that was intentionally different, easily remembered and something that one birder could recommend to another on the boardwalk without having to write it down. Hundreds of possible names later, we landed on the old New England name for the American Bittern based on the “dunk-a-doo” sound the bird makes from its secretive place in the marsh.”

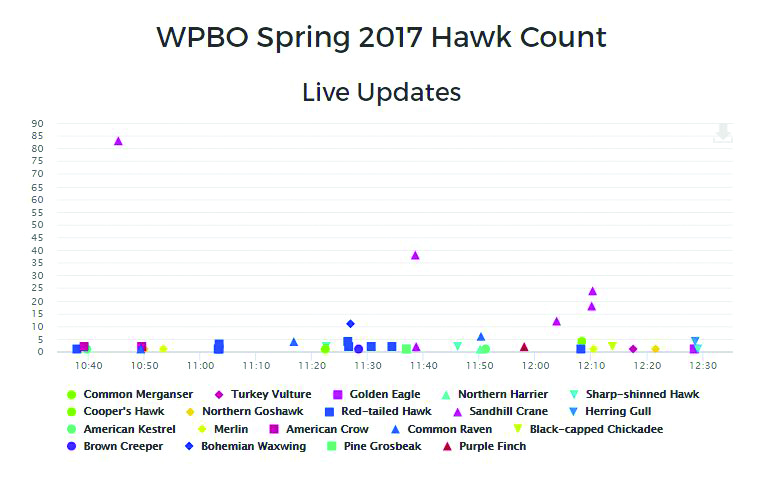

The app has a count interface featuring rows of buttons with species’ names that are similar to cell counters biologists have used for decades. Counters tap buttons to input data. Weather, flight information and other data can be entered on a separate metadata page. The app works with or without internet connection. If cellular reception is available at a count site, the tablet can be connected to the internet to provide live data broadcasts and integrate with other data collection systems.

For researchers like Haas, a veteran of waterbird counts ranging from WPBO, Cape May and Monterey Bay, Dunkadoo is an exciting new tool that will help his team modernize migration research in Michigan. Scientific observation efforts first occurred at Whitefish Point in 1912, initiated by Norman Wood and the University of Michigan’s Museum of Zoology. The first formal bird banding projects at Whitefish Point began in 1966. In 1976, Michigan Audubon established a Whitefish Point Committee, which resulted in the official creation of Whitefish Point Bird Observatory in 1979. Since that time, WPBO has been staffed by dedicated professionals and volunteers, and was led by a volunteer-board until 2016, when Michigan Audubon assumed ownership of the program after years of partnership.

“I mark the use of this new technology as an important evolution to the long tradition of research that has always occurred at Whitefish Point,” said Haas. “We are eager to utilize this tool in our commitment to maintaining a high standard of important historical bird migration data for the Great Lakes region. We also look forward to providing an innovative experience for our supporters across the globe with live data available during each day’s count.” Users will also be able to access charts and graphs that provide additional details related to the count data.

“Given the remote location of Whitefish Point and the incredible avian monitoring work we conduct at WPBO, the ability to share live updates of sightings with our members, birders, and the public is really exciting — it brings bird activity of WPBO to life in new, important, and really useful ways,” said Heather Good, Michigan Audubon’s executive director. The real-time data provided by the Dunkadoo application may be accessed on Whitefish Point Bird Observatory’s website at www.wpbo.org. To learn more about Dunkadoo, visit www.dunkadoo.org.