As is the case every spring, working in the woods at night at Whitefish Point for two and a half months starting in mid-March presents challenges, struggles, and many rewards. The weather was particularly unsettled for the first month and a half, and the snow hung on with a vengeance. We were effectively wearing the same gear in mid-May as we were on the first night of the season due to an unusually cold April and start of May. Sparring with the weather is worth the effort, as we study these silent flyers and provide insight into the movements of bird species that so many describe as magical.

As is the case every spring, working in the woods at night at Whitefish Point for two and a half months starting in mid-March presents challenges, struggles, and many rewards. The weather was particularly unsettled for the first month and a half, and the snow hung on with a vengeance. We were effectively wearing the same gear in mid-May as we were on the first night of the season due to an unusually cold April and start of May. Sparring with the weather is worth the effort, as we study these silent flyers and provide insight into the movements of bird species that so many describe as magical.

Despite spending two decades as the spring owl banders, we really did not know what to expect this year with the owl migration. Last year we experienced a particularly productive season that produced an unexpected peak of Northern Saw-whet Owls and a record number of Long-eared Owls. Although we were slightly disappointed in the Northern Saw-whet Owl (NSWO) numbers this year, it proved to be a relatively good season. We banded a total of 734 owls and recaptured 46 previously-banded owls. The 734 new owls comprised 462 NSWO, 12 Boreal Owls, 240 Long-eared Owls, and 20 Barred Owls. The 20 barreds represent the highest total banded in a spring season at the Point. The 46 recaptures were 41 NSWO, four long-eareds, and one barred. In addition to the owls, we banded three Eastern Whip-poor-wills this spring.

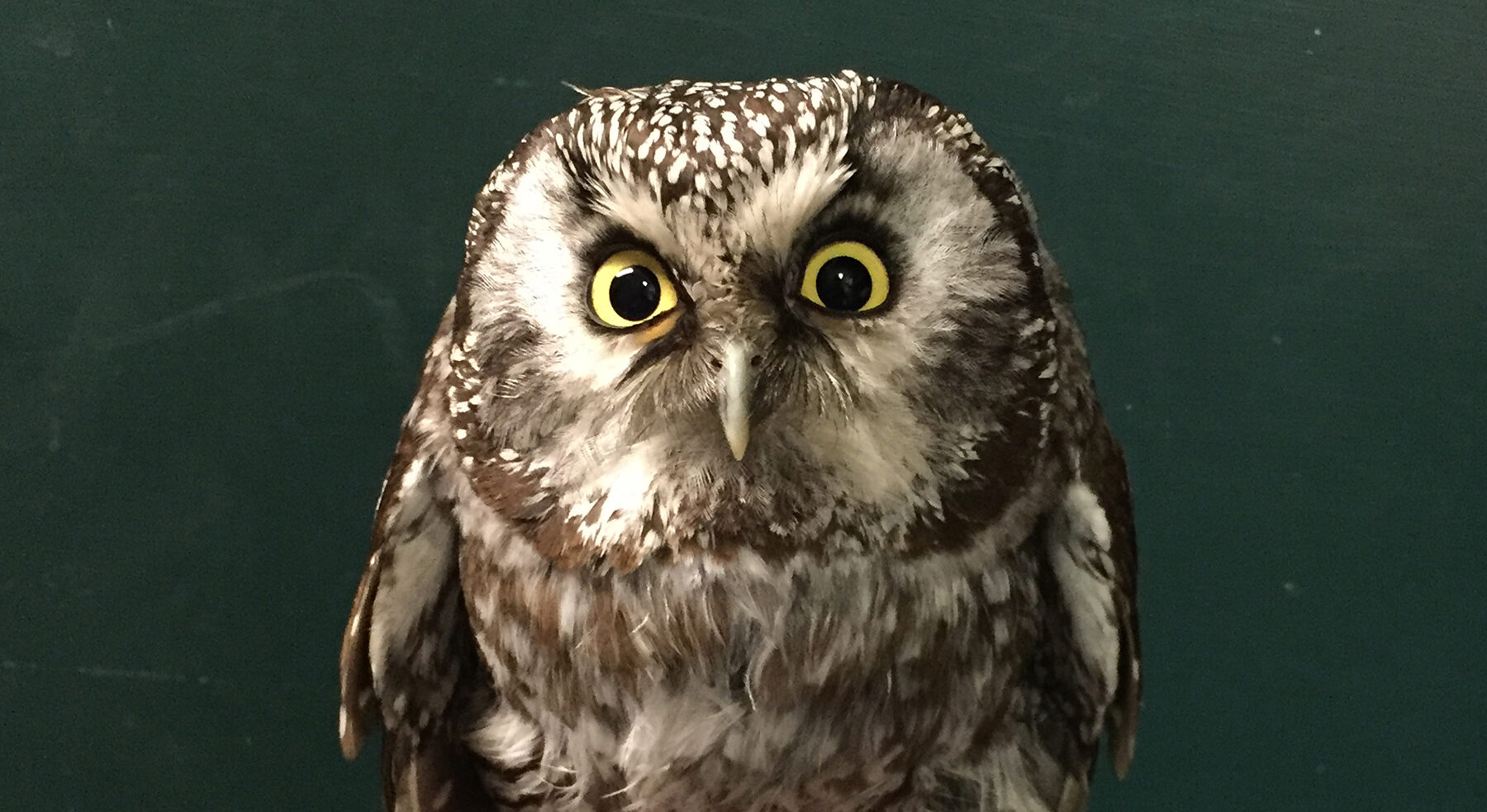

One of the 20 Barred Owls banded at WPBO this spring — a record for a spring banding season at the Point.

If you are a regular reader of the Jack Pine Warbler, you may remember us mentioning that NSWO numbers have been less predictable in recent springs. The relationship between the number of juveniles we band in the summer and the number we catch the following year on their first spring migration reversed itself in 2017 and 2018, then returned to what is expected in spring 2020. The most recent surprise in summer was an unexpected peak in reproductive success in 2020. The high reproductive success was reflected in the number of NSWO we banded last spring and again this season. Of the 952 NSWO banded last spring, 676 (71%) hatched in 2020. Of the 462 NSWO banded this spring, 197 (39%) hatched in 2020. Unfortunately, this is the last spring that molt patterns will allow us to determine that a NSWO hatched in 2020.

Coming off of last spring’s North American record season of 465 Long-eared Owls (LEOW), we would not have been surprised if their numbers crashed to particularly low numbers this spring. Therefore, we were very pleased with the 244, including the four recaptures this spring. We are still excited by the success of changes we made to our protocols in 2015, such as adding an LEOW audiolure, which increased LEOW numbers. During the 27 years before those changes, a total of 1,492 LEOW were banded here in the spring. In the eight years since implementing those changes, we have banded 2,017 LEOW. Prior to 2015, the highest number of LEOW banded in North America in a migratory season was 176, which just happened to be in Chris’s first season here in spring 1999. We always remind ourselves that the owls migrate through Whitefish Point whether or not we, or anybody else, is here to witness it. We feel incredibly fortunate to be the ones who get to witness their migration here so intimately and are gratified to have dramatically increased the productivity of WPBO’s long-term spring owl research.

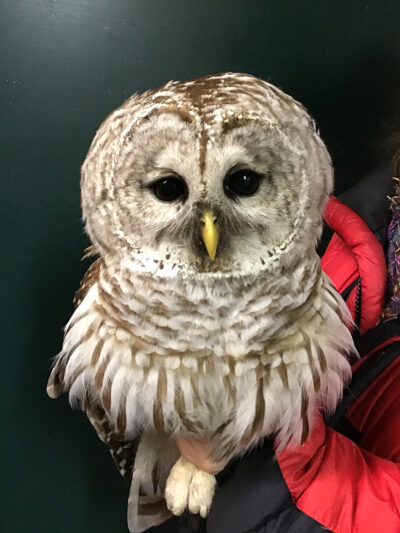

One of the 12 Boreal Owls banded at WPBO this spring.

Boreal Owl numbers continue to be low despite changes to protocol that have resulted in higher numbers for other owl species.

Boreal Owl numbers have been alarmingly low since 2009. Boreal Owl irruption years produced 163 and 114 in the springs of 1988 and 1992, respectively. Since 1992, irruption years have only produced numbers in the seventies. Since adding the NSWO audiolure to the protocol in 2007, the average number of NSWO banded per spring season went from 63 to 572. Since adding the audiolure for LEOW, numbers went from an average of 55 to 252. Unlike the NSWO and LEOW, we never saw an increase in boreal numbers after adding an audiolure for the species, and since banding 78 boreals in spring 2013, their highest total was 20 in 2018. As much as we hope their numbers eventually rebound, the possibility that we and future generations of owl banders here may never see them in the numbers we experienced just nine years ago is dispiriting.

Future banding efforts at Whitefish Point will continue to shed light on the population and dispersal of these birds that play a critical role in the ecosystem, such as helping to keep rodent populations down.

In addition to the birds, we are always amazed to see many of the amphibians here begin to emerge and make their way to the ponds while there is still several feet of snow covering most of the ground. We observed spotted salamander, blue-spotted salamander, four-toed salamander, eastern newt, wood frog, green frog, Cope’s gray treefrog, and spring peeper this spring.

We enjoyed visits from Waterbird Counter Alison Világ and former crew mates Tori Steely, Karl Bardon, Tim Baerwald, and Cory Gregory. As always, we thank all of you who support Michigan Audubon’s owl research at WPBO. We say it after each of our seasons, but it would truly be impossible without your generosity.

~ by Chris Neri and Nova Mackentley, WPBO Spring Owl Banders

Nova Mackentley and Chris Neri are a legendary pair of raptor banders living at Whitefish Point. In addition to regularly leading the owl banding program every spring at Whitefish Point Bird Observatory, they are accomplished nature photographers.

This section of the Jack Pine Warbler is dedicated to Michigan Audubon’s Whitefish Point Bird Observatory and features three articles illuminating the research conducted at WPBO this spring. This work focused on waterbirds (April 15–May 31), raptors (March 15–May 31), and owls (March 15–May 31).

As one of the three pillars of Michigan Audubon’s mission, research is at the heart and soul of what we do and integral to our value proposition. Whitefish Point ranks among North America’s most significant avian migration sites, and the observatory’s long-term research programs provide a picture of species dispersion, populations, demographics, movement, and more. This research is made possible through donations to Michigan Audubon that support our efforts to engage highly talented individuals to perform this work.

WPBO is located just north of Paradise, Michigan, along the shore of Lake Superior. The outdoor spaces of WPBO are open daily from dawn to dusk year-round. You can learn more at www.wpbo.org.